Mental Wellness

Mental Wellness 2020

Jump to:

- How to communicate with someone who could be struggling with their mental health

- Reaching out when YOU are struggling

- What is Self-Compassion?

- The Dangers of the Status Quo

- What is Perfectionism?

- Another Perspective on Perfectionism

- Good Sleep Hygiene

- Resources to Practice Good Sleep Hygiene

- Online Mental Health Resources

How to communicate with someone who could be struggling with their mental health

By Kelsie Ou

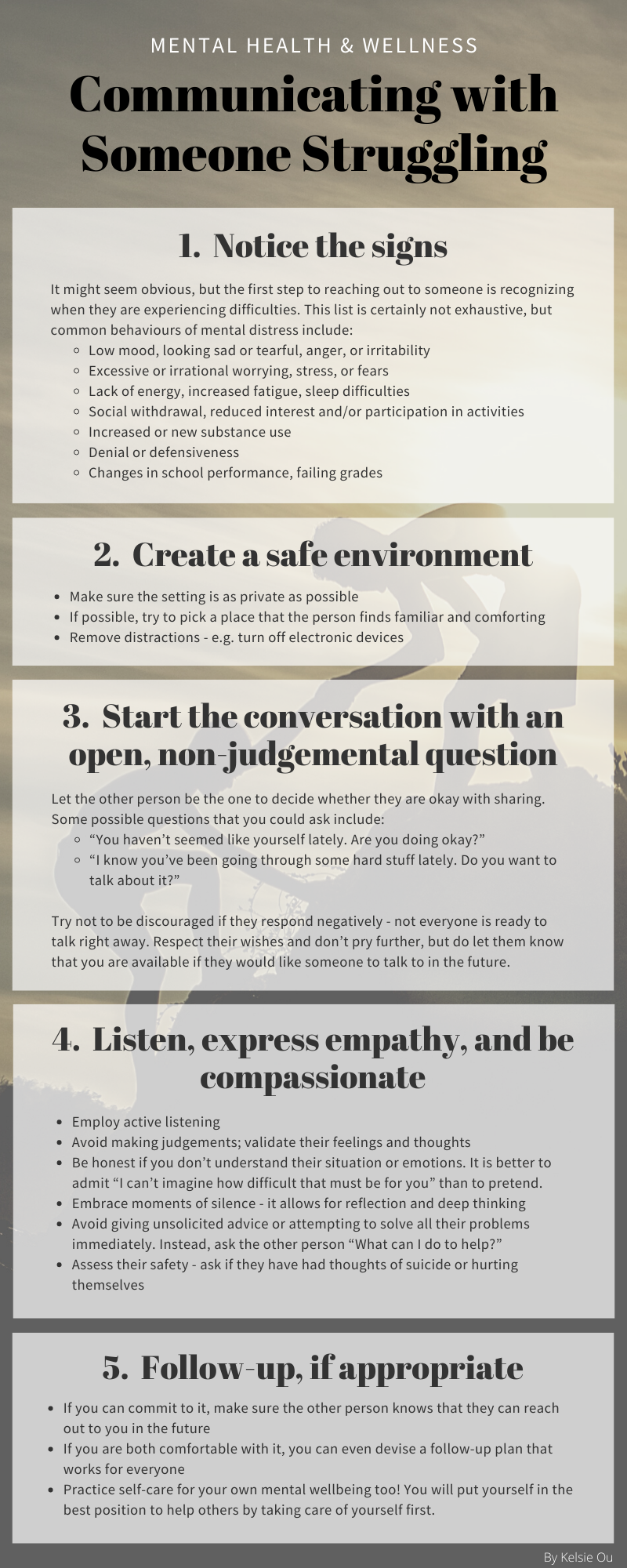

Mental health affects us all. At times, we look around and notice that our family, friends, or peers are struggling with their mental health. While we may want to help, it can feel like a daunting prospect. Below are some practical strategies you can use when reaching out to someone you care about who is experiencing difficulties with their mental wellness.

Reaching out when YOU are struggling

By Kelsie Ou

It can be difficult and intimidating - even terrifying - to reach out to someone else about your mental health. Finding someone to talk to is often one of the most important and helpful steps you can take in addressing your mental wellbeing, but we are rarely ever told HOW to do it. If you are struggling, here are some tips that might make opening up feel less scary, uncomfortable, and confusing.

- The Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention’s list of crisis centres and hotlines.

- Betterhelp is an online service that offers therapy and counselling with licensed therapists.

What is Self-Compassion?

By Karine Gou

The simplest way to understand self-compassion is to reflect on how we show compassion to others. The process begins with recognizing their emotions and responding to them. We tend to also offer them understanding and kindness in times of suffering rather than judging them harshly. This show of empathy highlights our capacity to go through hardships, and to perceive the latter as a shared human experience.

To further illustrate this, Dr. Kristin Neff, one of the pioneers in research looking at self-compassion, breaks down self-compassion into three elements:

- Self-kindness (and not self-judgement): recognizing that failures and shortcomings are inevitable, and accepting them with sympathy and kindness as opposed to self-criticism and feelings of inadequacy.

- Common humanity (and not isolation): avoiding feeling trapped with one’s negative emotions, and recognizing that suffering is shared by the human collective, which allows us to put things into perspective.

- Mindfulness (and not over-identification): striking a balance by staying receptive to negative feelings all while avoiding ruminating over them.

It is important to note that self-compassion is not synonymous with:

- Self-pity, which puts us at risk of being overly absorbed with our own miseries, thus exacerbating the feelings of loneliness.

- Self-indulgence, which tends to promote temporary pleasures; self-compassion favors instead long-term reflection and wellbeing.

- Self-esteem, which focuses on self-worth and comparisons with others, and fluctuates depending on our most recent victories or failures; regardless of one’s traits or accomplishments, everyone deserves compassion.

Why is Self-Compassion Important?

Many researchers have looked at the impact self-compassion can have on healthcare learners’ wellbeing and practice.

In terms of mental health, self-compassion is associated with lower rates of self-harm and suicidal ideation.1 Applying the common humanity mindset described above can increase the sense of belonging, and thus minimize feelings of loneliness and as a result, the risk of depression.2

Moreover, research on medical learners has demonstrated the relationship between mastery goals and self-compassion. Mastery goals are defined by the motivation behind acquiring competences, and can be divided into two types: mastery approach and mastery avoidance goals. Mastery approach goals refer to approaching success with the “motivation to improve or gain competence”, and are associated with “deep processing, error tolerance, perseverance and enjoyment of learning”. On the other hand, mastery avoidance goals are characterized by avoiding failure or “being incompetent or not doing worse than one has done in the past”, and are associated with “disorganized learning, psychological ill-being, and avoidance of help-seeking”. Not surprisingly, an article shows that practicing self-compassion is associated with mastery approach goals whereas lacking self-compassion leads to the endorsement of mastery avoidance goals.3 Another paper highlights how medical students who achieve mastery approach goals are more protected against burnout-related exhaustion and more engaged in their studies.4 It becomes clear that in our clinical settings where a competency-based learning model is increasingly favored, practicing self-compassion can improve not only our health, but also our capacity in providing care for others.

How can we be kinder to ourselves?

First, it is useful to reflect on the following questions to assess where we stand:

- Do I set unrealistic goals, and am I frustrated with myself when I do not achieve them?

- Do I respond poorly to criticism?

- Do even small mistakes seem disastrous?

- Do I abandon things quickly when I cannot live up to my expectations?

- Do I get so anxious about being perfect that I procrastinate from starting things at all?

Practicing self-compassion entails stopping to recognize our fears, anxiety, worries and judgemental thoughts: “This is hard for my right now. What can I do to feel better?” This reflection helps us embrace them as opposed to erasing them or sweeping them under the rug.

Engaging in this change of mindset can be difficult as it can open the door to past struggles and memories. Dr. Neff refers to this phenomenon as a “backdraft”, which can be illustrated with the following saying: “When we give ourselves unconditional love, we discover the conditions under which we were unloved.” In these moments, it is crucial to take a step back, reassess things and allow ourselves to take small steps towards self-care, such as by starting with small acts of self-love:

Ultimately and most importantly, we should modify our behaviors and ways not because we feel inadequate or unacceptable, but because we care about ourselves. In the same way that we have looked at the meaning of self-compassion by examining how we show compassion to others, one of the best tips to practicing self-compassion I can leave you with is to imagine speaking to ourselves as we would speak to others: as we would not chastise a friend or family member for a mistake, why would we treat ourselves that way?

References:

- Cleare, S., A. Gumley, and R.C. O'Connor, Self-compassion, self-forgiveness, suicidal ideation, and self-harm: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Psychother, 2019. 26(5): p. 511-530.

- Korner, A., et al., The Role of Self-Compassion in Buffering Symptoms of Depression in the General Population. PLoS One, 2015. 10(10): p. e0136598.

- Babenko, O. and A. Oswald, The roles of basic psychological needs, self-compassion, and self-efficacy in the development of mastery goals among medical students. Med Teach, 2019. 41(4): p. 478-481.

- Babenko, O., et al., Contributions of psychological needs, self-compassion, leisure-time exercise, and achievement goals to academic engagement and exhaustion in Canadian medical students. J Educ Eval Health Prof, 2018. 15: p. 2.

The Dangers of the Status Quo

By Audrey Le

Over the course of the past century, studies have shown that many medical students suffer from poor mental health, including but not limited to, increased depression, anxiety and suicidality.1,2 When we have tried to understand the causes, one that gets brought up repeatedly, is that of medical culture.3

So what exactly is medical culture? Well, a culture is a set of values or beliefs that shape an individual or a group. Medical culture thus encompasses the values or beliefs that shape individuals and groups within the medical profession.

As students, we often sense the pressures of this culture trying to dictate the way that we should think, act and feel. It starts from the very first day that we enter medical school. At orientation, we are welcomed and then, immediately reminded that we should feel extremely privileged because we were “the chosen ones”. We are the ones that proved ourselves to be extraordinary enough to enter this prestigious profession and we must never forget that. As future physicians, it is expected that we perform and sacrifice ourselves for the sake of our patients.

These beliefs are heavily ingrained and though I cannot deny their role in the nature of our careers, they also serve as a constant medium for resistance to change within our culture. Whenever discussions about reducing work hours to reduce student burnout arise, there is always immediate shame that follows. We are made to feel ashamed for talking about our suffering. We are made to feel like we are the problem, for being exhausted, for being burnt out and for demanding change that will better our system. We “must suck it up” because older generations of physicians got through it and they survived. A broken record then plays, “if I had to go through that, then so should you”. They got through it, indeed, but at what emotional costs?

It is almost as though, by suffering less, we would somehow render their experience more unfair. If we suffer less, then that must mean that we will never amount to being as competent. However, these ring like excuses because there have been studies that have shown how burnout decreases physician empathy and how that leads to poorer patient outcomes.4 So, my question is: if medicine is a field where we pride ourselves in our advancements, how can we continue to imitate the past and not address the issues that are preventing us from moving towards a collective betterment?

Even to this day, there still exists a huge stigma surrounding student mistreatment. Because it is extremely prevalent, mistreatment is regarded as just being part of the common medical student experience. Mistreatment has been shown to be one of the leading causes of medical student burnout and yet, it is still prevalent to the point that most, if not all, medical students will experience it at least once during their training. 4 The current approach to this issue seems to primarily aim at teaching students how to hone their own individual resilience. Whether that be, by screening for resilience in medical school applications or through implementing wellness and resilience training into academic curriculums. Although these are all valuable tools, this approach puts a great deal of emphasis on the individual student’s capacity to overcome adversities, rather than adequately addressing the overarching medical culture that created those adversities in the first place. I guess it is easier to try to induce change at the individual level than at a cultural one.

One study showed, that while students displayed resilience in response to life and death situations that were part of clinical encounters, they did not have that same resilience in response to mistreatment; instead, they experienced higher depression and stress. The difference between the responses to these two scenarios is thought to be due to one event being an unavoidable part of a student’s professional development, whereas the other, served no other purpose than to destroy their sense of wellbeing.5,6

I think that in order for medical culture to change for the better, the status quo needs to be challenged. We have to, as a collective group, regardless of our places in the hierarchy, empathize with one another and think critically about our own, engrained beliefs. Mental health in our community can no longer be sacrificed in order to maintain the status quo.

References:

- Strecker EA, Appel KE, Palmer HD, Braceland FJ. Psychiatric studies in medical education, II: neurotic trends in senior medical students. Am J Psychiatry. 1937;93(5):1197-1229.

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis.JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17324

- Slavin SJ. Medical Student Mental Health: Culture, Environment, and the Need for Change. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2195–2196. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16396

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an Educational Program in Mindful Communication With Burnout, Empathy, and Attitudes Among Primary Care Physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1384

- Cook, A. F., Arora, V. M., Rasinski, K. A., Curlin, F. A., & Yoon, J. D. (2014). The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(5), 749–754. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000204

- APA Haglund, Margaret E.M. MD; aan het Rot, Marije PhD; Cooper, Nicole S. PhD; Nestadt, Paul S.; Muller, David MD; Southwick, Steven M. MD; Charney, Dennis S. MD Resilience in the Third Year of Medical School: A Prospective Study of the Associations Between Stressful Events Occurring During Clinical Rotations and Student Well-Being, Academic Medicine: February 2009 - Volume 84 - Issue 2 - p 258-268 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819381b1

What is Perfectionism?

By Karine Gou

Perfectionism is may already be familiar to most as it is often a trait found in the medical student population. It is however a multidimensional concept, which can be divided into different branches.

To begin, perfectionism can be either adaptive or maladaptive. We often described adaptive perfectionists as being “achievement-oriented”: they enjoy the challenges that come with problem-solving and focus on achieving their goals. On the other hand, maladaptive perfectionists tend to unfortunately set unrealistic goals or standards, and struggle with self-criticism as well as concerns on making mistakes and receiving negative feedback from others. As such, this unhealthy form is described as “failure-oriented”. Author Julia Cameron in The Artist’s Way describes maladaptive perfectionism as “a refusal to let yourself move ahead. It is a loop – an obsessive, debilitating closed system that causes you to get stuck in the details of what you are writing or painting or making and to lose sight of the whole.”

The American Psychological Association divides maladaptive perfectionism into three different types:

- Self-oriented: when one’s perfectionistic motivations comes from placing unrealistic expectations and standards on oneself.

- Socially prescribed: when one’s perfectionistic motivations are motivated by the perceived unrealistic expectations from others.

- Other-oriented: when one places unrealistic expectations and standards on others, thus possibly prompting them to develop perfectionistic motivations of their own.

What has research shown?

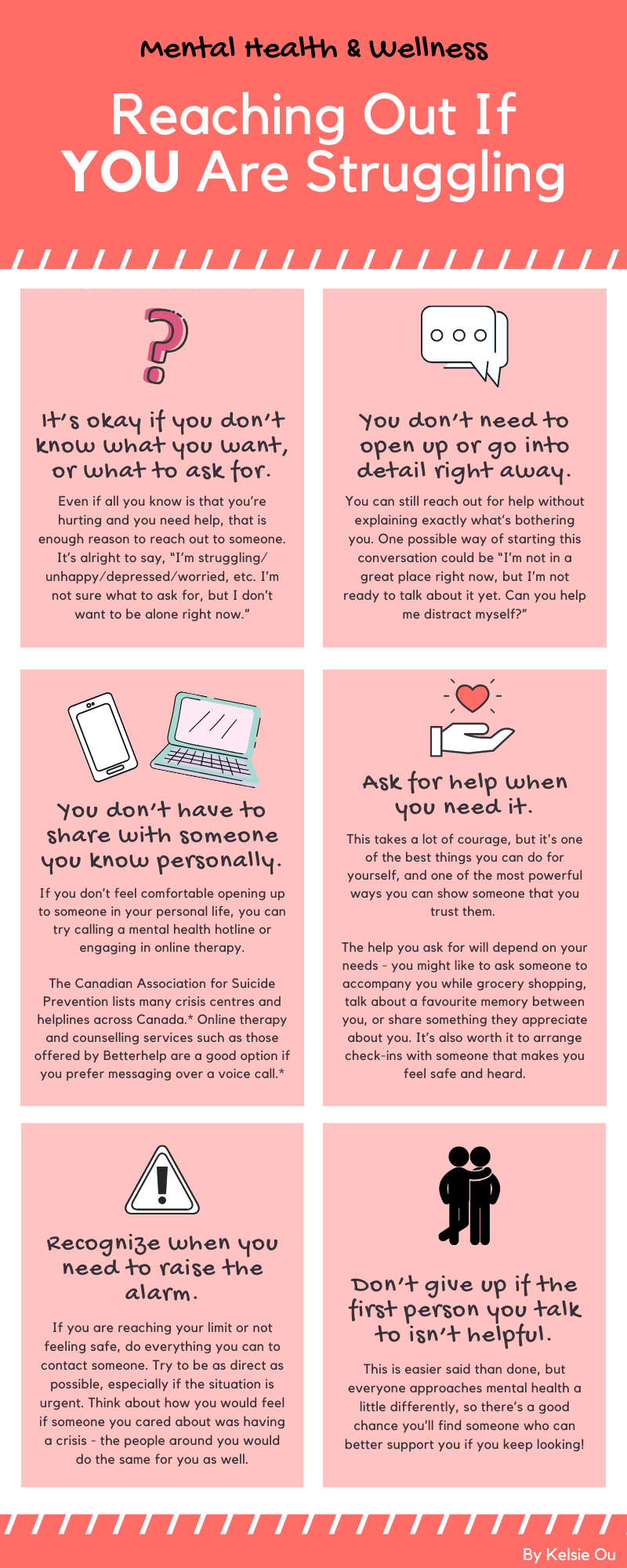

A study looking at the relationship between self-efficacy, socially prescribed perfectionism and academic burnout in medical students concluded that the risk of burnout is higher in students who tend to be socially prescribed perfectionists with low self-efficacy. The perfectionist tendencies could also negatively impact academic self-efficacy itself, thus increasing the risk of burnout. The article defines self-efficacy as the ability to persevere despite obstacles encountered when completing a challenging task; it is linked to lower levels of anxiety as well as better self-control abilities [1]. Furthermore, another study looked at the relationship between dysfunctional thoughts, negative feelings and poor mental health in pre-clinical medical students, and concluded that those who met criteria for maladaptive perfectionism were “more likely to report greater feelings of shame/embarrassment and inadequacy” than those who did not. Those who reported feeling those emotions were “significantly more likely to report moderate/severe levels of depression symptoms and moderate/high levels of anxiety symptoms” than those who did not. The article provides the model below to illustrate how these elements relate to each other, and how they can feed into one another [2].

How can we try to overcome maladaptive perfectionism?

Bringing a positive change to our maladaptive behaviors is of course easier said than done. An article highlights that “psychological practitioners often seek to directly change the form or frequency of clients’ maladaptive perfectionist thoughts, because such thoughts predict future depression”. However, changing our “relationship to difficult thoughts, rather than trying to change the thoughts directly could be just as effective” [3]. This idea links back to our last piece on self-compassion, in which I mention that becoming mindful of these behaviors and thoughts and responding to them with care and kindness rather than suppressing or fighting them is more favorable. After all, as Dr. Kristin Neff, a specialist in research in self-compassion, says, “we can’t always control the way things are”, but we can remember that “imperfection is part of the shared human experience”.

To help start practicing self-compassion, Dr. Neff offers free exercises and tips as well as a list of guided meditations on her website, accessible at the following link: https://self-compassion.org/category/exercises/#exercises

References:

- Yu, J.H., S.J. Chae, and K.H. Chang, The relationship among self-efficacy, perfectionism and academic burnout in medical school students. Korean journal of medical education, 2016. 28(1): p. 49-55.

- Hu, K.S., J.T. Chibnall, and S.J. Slavin, Maladaptive Perfectionism, Impostorism, and Cognitive Distortions: Threats to the Mental Health of Pre-clinical Medical Students. Academic Psychiatry, 2019. 43(4): p. 381-385.

- Ferrari, M., et al., Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLoS One, 2018. 13(2): p. e0192022.

Another Perspective on Perfectionism

By Audrey Le

We often hear medical students being described as “the cream of the crop”. Applying to medical school is a rigorous process and the students who end up being admitted are supposed to be exemplary. Naturally, this process selects students who hold themselves to extremely high standards in every aspect.

Although this ambition can lead us to achieve excellence, it doesn’t come without a price to pay – that price is sometimes our own mental health. We carry our perfectionist mentality into medical school and hold ourselves to standards that are often just short of being impossible. Even on the wards, it shows that we cannot forgive ourselves for making mistakes. We cannot forgive ourselves for not knowing the answer to every question that the attending asks. We cannot forgive ourselves for not publishing 50 research articles while we spend 50-60 hours in the hospital every week.

I used to be someone who resented myself whenever I made mistakes and I frequently got frustrated whenever I couldn’t live up to my own impossible expectations. I remember once getting a concussion early on in medical school and being miserable because I suddenly couldn’t study the way that I used to. At the time, this led me to really struggle with my own mental health. I remember mustering up the courage to finally talk to someone and to this day, their words still resonate with me every time I feel myself start to spiral into my perfectionistic thoughts again. This person suggested that I should try talking to myself the way that I talk to the people that I love. Would I tell my loved ones that I thought they weren’t good enough? Would I tell them that they should be studying and still excelling academically right after having a concussion?

The answer to both of those questions is an obvious no. However, I think it is definitely more difficult to offer ourselves the same kindness and compassion that we so naturally offer to others. Ultimately, I learned that being conscious of my own neurotic thoughts was a powerful tool. Once we become aware of these thoughts, it becomes much easier to stop them in their tracks. Now whenever that the negative voice in my head tells me that I am worthless because I made a mistake, I acknowledge the thought and try to counter it with a helpful statement instead. I tell myself that, “it’s okay to make mistakes, you did your best. This mistake doesn’t define you”. Sometimes, I have to reiterate it several times throughout the day and that’s okay. The irony of this approach is that practice does make perfect. Sometimes, our perfectionistic behaviours can become so engrained that we might not even notice them anymore. However, overtime, it does become easier to recognize and to fight them (after a lot of active work, however!). It takes a lot of courage to face them head-on, but I believe that this is the only way that we can liberate ourselves from the power that they exert over us.

Good Sleep Hygiene

By Randi Mao

What is Sleep Hygeine?

Up to 25% of people can experience sleep difficulties, including troubles with falling asleep, achieving adequate sleep duration or satisfying sleep. As such, good sleep hygiene is an essential component to enhance good sleep and offer a long-term solution to sleep difficulties. Therefore, sleep hygiene describes good habits and practices necessary for good nighttime sleep quality and daytime alertness.

Why is Good Sleep Hygiene Important?

Sleep is a crucial state that helps both mental and physical health. Here are some key benefits of a good night’s rest:

- Reduces stress and cortisol levels

- Positive impacts on memory and mood

- Increases energy levels, concentration and performance during the day

- Reduces inflammation and risks of heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, obesity and Alzheimer’s

- Better ability to cope with pain

- Cellular recovery during sleep

- Can prevent depression

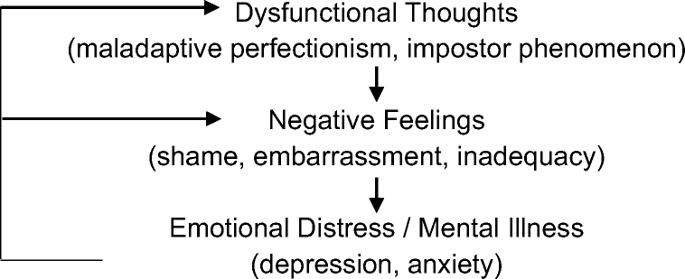

Recommended Hours of Sleep by Age:

Read more here: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/press-release/national-sleep-foundation-recommends-new-sleep-times

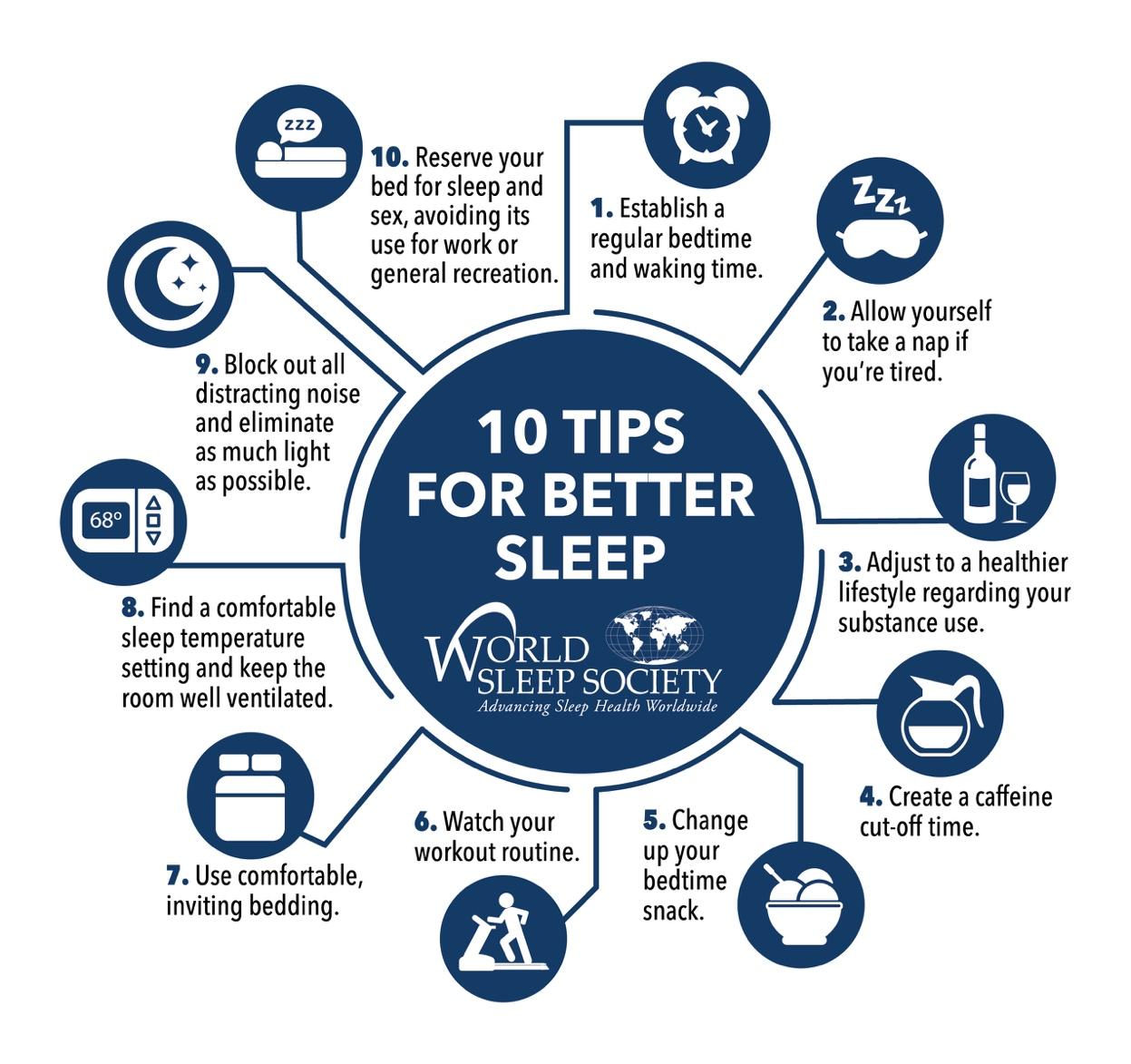

Tips for Good Sleep Hygiene!

Source: https://worldsleepday.org/10-commandments-of-sleep-hygiene-for-adults

- Establish a regular bedtime: this includes developing a regular nightly routine that helps your body recognize that it is bedtime! You could partake in reading, light exercise or even a nice skincare routine to get you in the mood.

- Take naps when you’re tired: try to limit naps to 20-30 minutes to help improve mood and performance!

- Adjust to a healthier lifestyle with substance use: it is best to avoid stimulants such as coffee and nicotine near bedtime. Excessive alcohol can help you fall asleep faster but may disrupt the latter half of your sleep when the body starts processing it. Moderation is key!

- Create a caffeine cut-off time: it is best to cut off caffeine 6 hours before bedtime.

- Change your bedtime snack: it is best to avoid heavy, fried, spicy, sweet, and citrusy foods before bed. Light snacks are fine though!

- Workout routine: a short period of aerobic exercise can also improve sleep hygiene. It is best to avoid intense workouts right before bedtime, but light exercises can be a great routine before bed.

- Use comfortable bedding: create a sleep environment that is warm and welcoming – perfect for a peaceful rest!

- Find an appropriate room temperature and proper ventilation: for optimal sleep, a bedroom should be kept cool at around 16-19°C. Humidifiers, fans and other appliances can help to maintain optimal room ventilation.

- Block out as many distractions as possible: consider using blackout curtains or sleep masks to block light sources. Ear plus or “white noise” machines can help to ward off noisy distractions.

- Reserve your bed as a space for sleep and sex.

Read more here: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/sleep-hygiene, http://www.anxietycanada.com/sites/default/files/SleepHygiene.pdf

Resources to Practice Good Sleep Hygiene

By Randi Mao

Websites/Software

SleepyTi.me - a website that serves as a sleep calculator! If you enter a wake-up time, it can automatically suggest times that you should fall asleep by.

Source: https://sleepyti.me/

Brain.fm – a website that features sound effect tracks that have been scientifically tested to help with sleep. Tracks can be customized to accommodate naps or even a full night’s sleep. A free trial is available, but it is primarily a premium service.

Source: https://www.brain.fm/

NOISLI – a great website that has noise loops of different sounds (water, rain, white noise) to help you get to sleep. This is also available as a paid app on both iPhone and android!

Source: https://www.noisli.com/

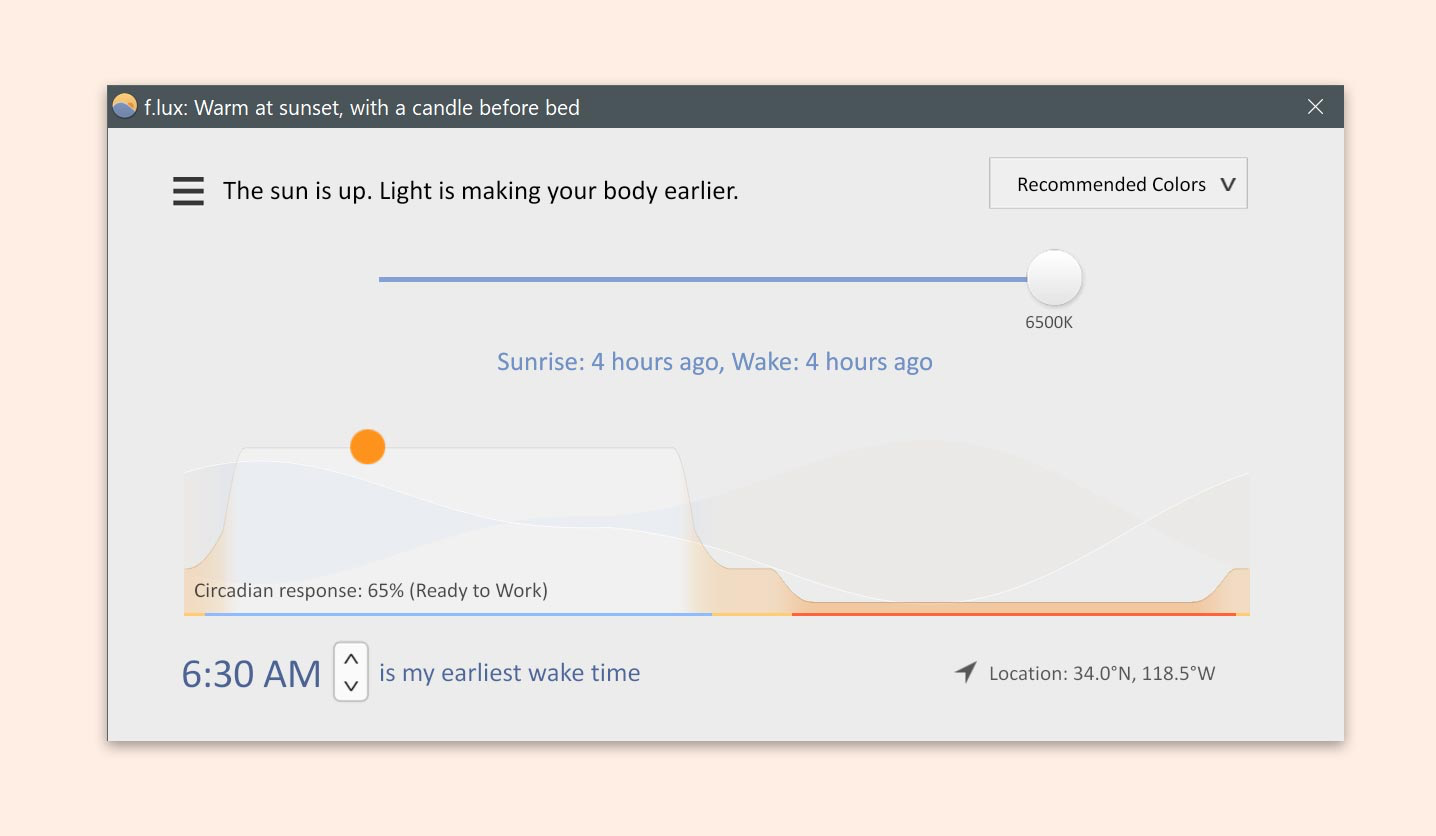

F.lux – A smart tool that automatically adjusts brightness on computer screens or devices according to the level of brightness in the environment. Screen brightness adjustments are also synchronized to the time of day, with the tool tinting screens to a warmer hue at night-time.

Source: https://justgetflux.com/

Apps

Relax Melodies – Free iPhone and Android app. Relax Melodies has a large selection of 100+ sounds that can put you right to sleep. There is also an option to overlay mindfulness meditations over the mix of sounds you create!

Sleep Cycle – Free iPhone and Android app. Sleep cycle is an app that helps to analyze sleep patterns (with graphs and statistics!) and serves as an alarm that wakes you up during your lightest sleep phase. The app even uses your phone’s microphone to analyze movements and vibrations during your sleep!

Sleep Time – Free iPhone and Android app. Sleep Time is another smart app that monitors movements to analyze sleep and sleep patterns and also has an alarm that wakes you during your lightest sleep phase! Sleep Time incorporates a feature that allows you to fall asleep to white noise or soundscapes.

Pillow – Free iPhone app. Another app that has sleep tracking capabilities (with the bonus of being able to connect to your Apple smart watch) and alarm features. This app also integrates with Apple’s Health app to measure that effect of health metrics on your sleep quality.

Relax and Sleep Well – Free iPhone and Android app. This app was created by clinical hypnotherapist and author, Glenn Harrold. Relax & Sleep Well includes four free meditation recordings that help put you to sleep and sleep well at night!

Source: http://www.relaxandsleepwell.com/

Online Mental Health Resources

By Portia Tang

There are lots of great lists of mental health resources. We’ve included links to 2 resources that are geared towards medical students. In addition, check out last year’s mental health wellness resources for additional recommendations on helpful apps and websites.

https://hslmcmaster.libguides.com/c.php?g=306766&p=2044909

McMaster University has a page of resources specifically for physicians. Their list includes information about the Physician Health Program (for those in Ontario) and links to programs addressing perfectionism, depression, and panic attacks. They also provide links to a CBT program and podcasts on mental resilience.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1vKy-N2oQOEdZJvyEghG4YDgoWIxyxSv46TS0HH21ZRY/edit#gid=0

This is a CFMS resource created for wellness support, including mental health, during Covid-19. It includes links to mental health apps such as Headspace and Calm, as well as online courses on wellbeing and managing anxiety. The document is meant to be a ‘live’ resource that is updated based on available resources.